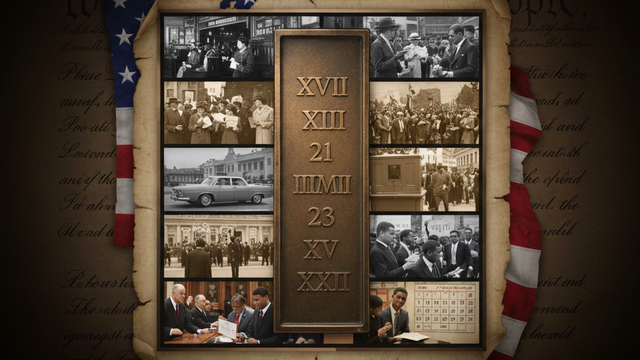

The United States Constitution has been successfully amended only 27 times since 1789. The most recent group of ten—Amendments 18 through 27—span a critical period from the Progressive Era through the late 20th century. These amendments are not isolated incidents; rather, they serve as legal landmarks reflecting the profound social movements, political crises, and evolving governmental needs of modern American history.

This analysis synthesizes the legal, social, and political significance of these amendments, highlighting how they collectively shaped the nation’s legal and civic landscape.

Phase I: Social Morality and Unique Reversal (18th and 21st)

The first of the final ten amendments, the 18th, was ratified in 1919 and marked a massive, national social experiment: Prohibition. Driven by powerful temperance advocates, the amendment outlawed the manufacture, sale, and transport of alcohol. However, the unexpected long-term impacts included a massive rise in organized crime and widespread non-compliance.

This unique failure led directly to the 21st Amendment in 1933, which repealed Prohibition. This remains the only time in U.S. history that an amendment was ratified solely to cancel a previous one, demonstrating the Constitution’s capacity to correct its own course under overwhelming public pressure and unforeseen negative consequences.

Phase II: Expanding Democratic Participation (19th, 23rd, 24th, 26th)

A defining trend among the last ten amendments is the sustained effort to broaden and protect the right to vote. These four amendments were direct responses to grassroots activism and civil rights movements, making the U.S. political system more inclusive.

- 19th Amendment (1920): Granted women the right to vote. This victory, hard-won by the suffrage movement, immediately enfranchised millions of women, fundamentally altering the American electorate.

- 23rd Amendment (1961): Extended presidential voting rights to residents of the District of Columbia, affording the capital city three electoral votes.

- 24th Amendment (1964): Outlawed poll taxes in federal elections. This was a critical component of the Civil Rights Movement, removing a significant financial barrier that had historically been used to suppress minority, particularly Black, voters in the South.

- 26th Amendment (1971): Lowered the national voting age from 21 to 18. Ratified at a time when many young men were drafted to fight in the Vietnam War, the argument “old enough to fight, old enough to vote” resonated widely, enfranchising another 11 million Americans in a rapid ratification process.

Phase III: Modernizing Government Operations (20th, 22nd, 25th)

Other amendments focused on fixing institutional problems and modernizing the structure of the federal government, particularly the executive branch, in response to crises and political challenges.

- 20th Amendment (1933): Known as the “Lame Duck” Amendment, it shifted the inauguration dates for the President and Congress closer to election day. This reduced the time outgoing officials (lame ducks) had to influence policy without accountability, thus improving governmental efficiency.

- 22nd Amendment (1951): Limited the presidency to two terms. This came after Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected to four terms and sought to ensure regular turnover and prevent any single individual from accumulating excessive power over decades.

- 25th Amendment (1967): Clarified the procedures for presidential succession and disability. Prompted by the uncertainties following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, this amendment established clear mechanisms for the Vice President to take over temporarily or permanently, ensuring government stability and continuity during crises.

Phase IV: The Principle of Accountability (27th)

The final ratified amendment, the 27th Amendment (1992), stands alone for its history. It requires that any law changing the compensation of Congress members cannot take effect until after the next election.

Originally proposed by James Madison in 1789 as part of the Bill of Rights, it failed to be ratified in the initial wave. It lay dormant for nearly two centuries until a renewed push for governmental accountability led to its final ratification 203 years later. It is a powerful example of the constitutional process maintaining continuity across vastly different eras.

Conclusion

The last ten constitutional amendments demonstrate that the U.S. Constitution is a living, though challenging to change, document. They reflect a movement away from social engineering (like Prohibition) toward institutional stability and, most significantly, towards greater democratic inclusivity. Achieving the high bar for ratification—a required consensus of two-thirds of Congress and three-fourths of state legislatures—underscores the significance of each successful amendment. As the nation faces ongoing debates about federal power and voting rights, these amendments provide a crucial roadmap of how political and social challenges can be addressed through the foundational legal document.

no matter what you say the positive outway the negatives, legalize drugs at least take a step by step approach start with pot and work from their think about it or at least have a national vote that goes for abortion too (no limited time period(